- Home

- Jim Defede

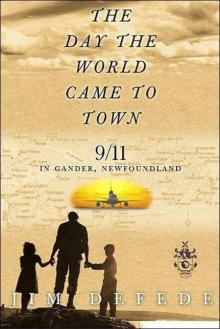

The Day The World Came To Town

The Day The World Came To Town Read online

The Day the World Came to Town

9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland

Jim DeFede

Dedication

For my mother, and in memory of my father

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Day One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Day Two

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Day Three

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Day Four

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Days Five and Six

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Where are you going?”

The man sitting next to me was curious, since we’d both been on the same plane from Miami to Montreal, and now, by coincidence, we were sitting next to each other on a connecting flight to Halifax, Nova Scotia. It was early February and he was on his way home after vacationing in the Caribbean.

“Gander, Newfoundland,” I said.

Because of the lack of a regional accent in my voice, the man could tell Newfoundland was not my home. “Why would anybody leave Miami to go to Gander in the middle of winter?”

This was certainly a reasonable question. When I had left Miami it was warm and sunny and about eighty-five degrees. The forecast in Gander called for temperatures somewhere around minus ten degrees Fahrenheit, with a windchill of minus thirty.

“Don’t get me wrong, amazing people in Newfoundland,” he quickly added. “I used to live there. Friendliest people you will ever meet. Strangest, too.”

The man was a civil engineer and he offered a story as proof. “We had a crew that was working in this remote town in the far northern end of the province,” he began. “The only way to reach this town was by airplane. There were no roads into it at all. And no hotels. So while the crew is working up there, they live with families in the area. The couple they were staying with was really nice, and at the end of the job the company, as a bonus, offered to fly them to Florida for an all-expenses-paid week-long vacation.”

The man laughed, recalling what happened next. “The couple turns it down,” he explained. “They say, ‘But we don’t know anyone in Florida, why would we want to go there?’ So we ask them if there is someplace they would rather go instead. And they name this town that was about twenty minutes away by plane. They had friends there they hadn’t seen in a while. And that’s what we did. We flew them to this nearby town, and the couple spent a week with their friends, and then we flew them home again. They said it was the best vacation they had ever been on. That’s the kind of folks Newfies are.”

He then added: “And you know what happened there on September eleventh?”

There are a few things everyone should know about Newfoundland.

First and foremost is how to pronounce it correctly. Few things are likely to make a native of this province surly faster than mispronouncing their homeland—a fact I was reminded of several times.

Newfoundland is not enunciated as if it were three distinct words, as in “New Found Land.” Nor is it pronounced as if it were somehow a Scandinavian colony, as in “New Finland.” Instead it is “Newfin-land.” The key is to say it very fast. One fellow offered me a simple mnemonic device: “Understand Newfoundland.” The words rhyme and the cadence is similar.

Over the centuries, Newfoundlanders have developed a style and language distinctively their own, an amalgam of working-class English and Irish, although in lilt and tone it leans a bit more toward the Irish. The people who originally settled here were not wealthy or well educated. They came for the fish. They were from towns along the southern coast of England—Plymouth and Bristol and Poole—and the west coast of Ireland, places like Ballybunion and Waterville and Galway.

Once they decided to stay in Newfoundland, they created their own style of speech that lives to this day, especially in the smaller outpost towns along the coast. It is more Shakespearean than contemporary. Sentences often end with the phrase “me dear” and “me lovely.”

Newfoundlanders employ an almost continuous third-person present tense in their speech. A phrase such as “I am a fisherman” would be “I is a fisherman,” or since Newfoundlanders contract “I is” into the single word “I’se” (which sounds like “eyes”), the phrase becomes “I’se be a fisherman.” The contractions are often a product of the speed with which they speak. The smaller the town, the faster the talk. There is even something called the Dictionary of Newfoundland English, a massive and definitive tome, which is now in its second edition and runs 847 pages.

It is also helpful to remember that Newfoundland is in a world of its own. Or at least its own time zone. Newfoundland is precisely one hour and thirty minutes ahead of U.S. Eastern Standard Time. So when it is 10 A.M. in New York, it is 11:30 A.M. in Gander. When it is noon in Los Angeles, it’s 4:30 P.M. in the provincial capital of St. John’s. No one else in the world is on Newfoundland time other than Newfies. Which, in a way, is appropriate.

Newfoundlanders are fiercely proud of their history and remain independent in their identity as Newfoundlanders first and Canadians second. A part of the British Empire since John Cabot landed there in 1497, Newfoundland only became a part of Canada in 1949. The margin of the popular vote in the referendum to join Canada as its last province was so slim that older Newfoundlanders still question the legitimacy of the election. Even today, many Newfoundlanders believe the central government in Ottawa has robbed them of their natural resources and cheated them out of financial well-being.

Newfoundland has an unemployment rate of more than 16 percent, the highest in Canada. Its timber industry is mostly gone, its mines are quickly becoming empty, and the fishing industry—once the lifeblood of Newfoundland—has been decimated, they believe, by the policies of the central government, which prevents small local fisheries from operating but signs treaties to allow foreign trawlers, with their massive nets, to literally scrape the bottom of the Grand Banks and carry off the province’s bounty.

Newfoundlanders live like a people under siege. Isolated on an island and powerless against the harshness of the weather, they have learned to count on one another for survival. Neighbor to neighbor. It is a mentality that has been fostered over centuries, since the earliest settlers realized the only way to survive in this desolate but beautiful outpost was to work together. Much of their music captures this spirit. One song in particular that Newfoundlanders love is an old tune called “There Are No Price Tags on the Doors of Newfoundland.”

Raise your glass and drink with me to that island in the sea

Where friendship is a word they understand.

You will never be alone when you’re in a Newfie’s home,

There’s no price tag on the doors in Newfoundland.

There will always be a chair at the table for you there,

They will share what they have with any man.

You don’t have to worry, friend, if your pocketbook is thin,

There’s no price tag on the doors in Newfoundland.

Their willingness to help others is arguably the single most important

trait that defines them as Newfoundlanders. Today, it is an identity they cling to, in part, because it is something that cannot be taken away from them.

There is a tale Newfoundlanders are fond of repeating. It is the story of the USS Truxton, an American destroyer, and its supply ship, the Pollux. On February 18, 1942, a violent storm forced the Truxton and the Pollux to run aground beneath the cliffs of the Burin Penisula. Both ships broke apart and 193 sailors drowned. But another 186 sailors were saved when the men from the towns of Lawn and Lawrence, at great peril to themselves, descended the icy cliffs to pull them to safety.

“Newfoundlanders are a different breed of people,” Gander town constable Oz Fudge told me. “A Newfoundlander likes to put his arm around a person and say, ‘It’s going to be all right. I’m here. It’s going to be okay. We’re your friend. We’re your buddy. We’ve got you.’ That’s the way it’s always been. That’s the way it always will be. And that’s the way it was on September eleventh.”

The events of September 11 were historic for many reasons. One of them was that the airspace over the United States was shut down, and every plane in the sky was ordered to land immediately at the nearest available airport.

“Get those goddamn planes down,” Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta shouted into a phone from a bunker under the White House.

By the time Mineta uttered those now well-publicized words, American Airlines Flight 11 had already crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, United Airlines Flight 175 had slammed into the South Tower, and American Airlines Flight 77 had struck the Pentagon. A short time later, a fourth plane, United Airlines Flight 93, would plow into a field in a rural area southeast of Pittsburgh. The official order to close U.S. airspace had been given by the Federal Aviation Administration at 9:45 A.M. (Eastern Daylight Time).

Mineta’s colorful outburst a few minutes later only added emphasis.

Never before in the ninety-eight-year history of American aviation had such a command been given. There were 4,546 civilian aircraft over the United States at the time, from private Cessnas to jumbo jets, and they all scrambled to find a place to land. Closing airspace had its most disorienting effect, though, on approximately four hundred international flights headed toward the United States, the majority of which were coming across the Atlantic from Europe.

While some of these planes were able to turn around, the only option for most was to land in Canada. Although officials in the United States were certainly justified in wanting to protect their own borders, they were effectively passing the potential threat posed by these planes onto their neighbor. Canadian officials had no way of knowing if any of these flights contained terrorists. In fact, Canadian and American law enforcement suspected there were terrorists lying in wait on some of these flights. Despite the risk, Canada didn’t hesitate to accept the orphaned planes.

More than 250 aircraft, carrying 43,895 people, were diverted to fifteen Canadian airports from Vancouver in the west to St. John’s in the east. American-bound planes were forced to land in Halifax, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Winnipeg, and Calgary. In each of these cities an army of volunteers and social service agencies came together to help the stranded passengers in any way possible—from offering them a place to stay or a change of clothes to cooking them meals and taking them sightseeing.

Countless stories could be written about the kindness shown in any of these cities. The focus of this book, however, and the purpose for my unseasonable trip this past winter, is Gander, located in the central highlands of Newfoundland. Thirty-eight planes landed there on September 11, depositing 6,595 passengers and crew members in a town whose population is barely 10,000.

For the better part of a week, nearly every man, woman, and child in Gander and the surrounding smaller towns—places with names like Gambo and Appleton and Lewisporte and Norris Arm—stopped what they were doing so they could help. They placed their lives on hold for a group of strangers and asked for nothing in return. They affirmed the basic goodness of man at a time when it was easy to doubt such humanity still existed. If the terrorists had hoped their attacks would reveal the weaknesses in western society, the events in Gander proved its strength.

DAY ONE

Tuesday

September 11

CHAPTER ONE

Clark, Roxanne, and Alexandria Loper, Moscow, September 10, 2001.

Courtesy of Roxanne Loper

Roxanne and Clark Loper were homeward bound.

Nearly three weeks had passed since they left their ranch outside the small Texas town of Alto and embarked on a journey to adopt a two-year-old girl in the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan. It was a journey more than fifteen months in the planning and saw the young couple race through airports, bounce along bumpy roads, and wind their way across the Ural Mountains. They dealt with bureaucrats in three different countries and spent their life savings, all for the sake of a child whose picture Roxanne had seen one day on the Internet. Every minute, every dollar, was worth it, though, because now they had Alexandria, and by dinnertime they’d be home.

Over the last seventy-two hours, the three of them had flown from Kazakhstan to Moscow to Frankfurt and were now on the final leg of their trip, a direct flight from Frankfurt to Dallas. They all felt as if they hadn’t slept in days. Shortly after takeoff, Alexandria climbed out of her seat and curled up on the floor to take a nap. Roxanne thought about picking her up and strapping her back into her seat, but she knew Alexandria liked sleeping on the floor. She felt comfortable there. It was something the child had grown accustomed to in the orphanage.

As the Lopers’ plane, Lufthansa Flight 438, proceeded northwest out of Frankfurt and climbed to above 30,000 feet, Lufthansa Flight 400 began preboarding its first-class passengers. Settling into her seat, Frankfurt mayor Petra Roth was excited about her trip to New York. That night there would be a party in honor of New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani. Roth and Giuliani had become friends during official visits to each other’s city, and Roth was happy to travel the 4,000 miles to pay her respects to the outgoing mayor.

Sitting near Roth was Werner Baldessarini, the chairman of Hugo Boss, who was flying to New York from the company’s corporate headquarters in Germany for Fashion Week—an eight-day spectacle of clothes and models in which more than one hundred of the world’s top designers show their latest wares in giant tents and on improvised runways. A good show at Fashion Week can guarantee the success of a manufacturer’s collection. On Thursday evening, Baldessarini would premier Hugo Boss’s Spring 2002 line at Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan. In addition to the financial implications of having a good show, this event was also important to Baldessarini for personal reasons. After twenty-seven years with Hugo Boss, he had made up his mind to retire in 2002. The news hadn’t been leaked publicly, but this would be one of his last shows and he wanted it to be a success.

While a flight attendant offered Roth and Baldessarini a glass of champagne before takeoff in Frankfurt, a few hundred miles away in Dublin, George Vitale was taking his seat in coach aboard Continental Flight 23. As one of the people responsible for protecting New York governor George Pataki on a day-to-day basis, Vitale had flown to Ireland in early September to make advance security arrangements for the governor’s visit there later that month. Unfortunately, a fresh round of violence in Northern Ireland caused the governor to abruptly cancel his trip, and the New York State trooper was told to come home.

If he had wanted to, Vitale could have stayed in Ireland to see friends and family. The forty-three-year-old is half Irish and he’s made several trips over the years to the Emerald Isle. This wasn’t a good time for a vacation, however. He had a number of responsibilities waiting for him at home in Brooklyn. In addition to being a senior investigator with the state police, Vitale was also taking night classes toward a degree in education. Assuming everything went smoothly, he’d be home in time for his class at Brooklyn College.

An hour after Vitale’s flight ascended into

the sky, Hannah O’Rourke stood outside the boarding area for Aer Lingus Flight 105 and cried as she hugged brothers and sisters good-bye. The sixty-six-year-old O’Rourke was born in Ireland’s County Monaghan, about forty miles north of Dublin, but had emigrated to the United States nearly fifty years ago. She made a good life for herself in America. Along with her husband, Dennis, she raised three children and now lived on Long Island.

In recent years, she’d returned to Ireland as often as possible to see her family. This time around, she spent three weeks in the countryside with her husband. She hated saying good-bye to her kin, but her family in America was eager for her to come home. Waiting to board the plane, O’Rourke dreaded the flight back. It was no secret she hated flying, especially over water.

The Day The World Came To Town

The Day The World Came To Town